This post is part 2 of a series of posts about an analysis of the Swedish language. Other parts are:

Part I: nouns

Verbs

Passive and deponent

Swedish has an interesting way of using verbs in a passive way. Where in English the form “<object> is being <verbed>” and in Dutch “<zelfstandig naamwoord> wordt ge<werkwoord>” are used, Swedish uses an inflection of the verb. So the English sentence “the doors are being closed” becomes “dörrarna stängs“. Stängs is a passive inflection of the verb att stänga (to close). Passive forms often end in an “s”.

Now the interesting thing is that there are a handful of verbs of which only the passive form is used, even though the meaning is active. Some examples are the verbs att hoppas (to hope) and att träffas (to meet). These verbs have no active form and are called deponent verbs. Before I started my analysis I could name a few, but I was wondering how many more there are. It turns out that there are 248 of them, out of a total of 8345 (≈3%) according to SAOL.

Groups

Swedish has multiple groups in which verbs are divided. Depending on how a verb is inflected, it belongs to a particular group. Wikipedia has a pretty elaborate article on this, but the basic idea is that there are 4 different groups: groups 1 and 2 are regular, group 3 are short verbs and group 4 are strong and irregular verbs.

I wanted to know how many verbs are there in each group, but unfortunately SAOL doesn’t contain this information. What I did was trying to find a list of verbs belonging to group 3 and 4 and infer groups 1 and 2 by looking at the present tense inflection of the verb. The present tense of a group 1 verb always ends in -ar and the present tense of a group 2 verb always ends in -er. For some verbs (mostly the deponent ones), I couldn’t figure out to which group they belong, so I marked them as unknown. Also, if you read the Wikipedia article, groups 1, 2 and 4 have subgroups, where group 4a for example contains the strong verbs and group 4b contains the irregular verbs, but since I didn’t have enough information, I only created 4 groups in my data set; 1, 2, 3 and irregular.

Now if we create a pie chart out of the data we get this:

As you can see, most verbs belong to group 1 and that about 88% of the Swedish verbs are regular. Slightly unfortunate is the fact that the irregular verbs (the ones you have to know by heart) are also verbs that are used quite often, but I guess frequently used verbs are irregular in many languages. Verbs like att vara (to be), att säga (to say) and att stinka (to stink) are all irregular for example.

Word length

Another thing that I wanted to know is how word length distributions are in Swedish. This is basically counting how long each word is and then graphing that. And it looks like this:

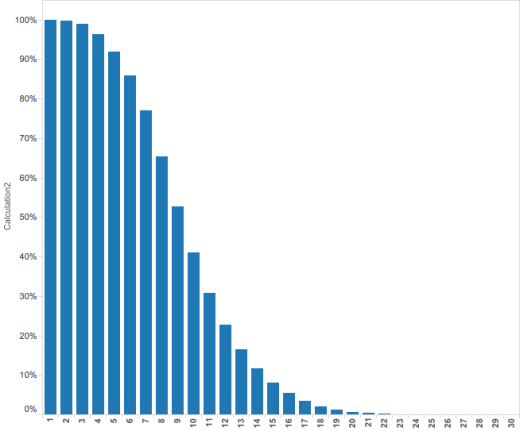

Here we see that about 12,5% of the words are 9 letter words. By changing this graph a little bit, we can understand how much words are larger than x letters:

Here we can see for example that about 53% of all swedish words is larger than 9 letters.

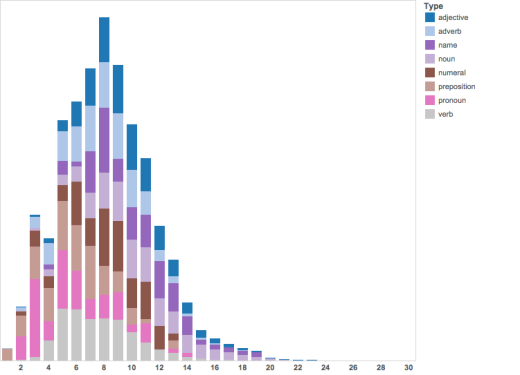

All of the words words in the Swedish language were used in the previous two graphs, but it’s also interesting to see how different types of words are distributed:

Here we can see some interesting things. Not unexpected, nouns follow the same curve as all the words, because it’s the biggest group of words and contribute much to the shape of the curl. But verbs and prepositions are generally smaller than nouns. Also, there are more 3 letter pronouns than pronouns of other sizes.

Normalizing the data by graphing what share of each group contributes to each word lengths, the graph looks like this:

Here we see that the amount of 8 letter words seems to be quite equal for all the groups, but that 24% of the pronouns is 3 letters long, but only 1% of the adjectives is.